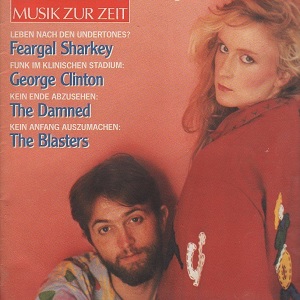

Wendy’s feet

Wendy’s feet

What is it that makes us listen to music? Is it to escape our own loneliness? Music comes in the night and says ‘you’re not alone’. All the same, we enjoy being lonely, to play the tragic hero, different from the others. So music must also tell us “you’re not like the rest, that’s why you’re alone, and because you’re different only you and you alone can understand me; because I’m the only one different in the same way as you. And so, tonight, we are sole allies.”

The duties of pop music with respect to the petty-bourgeois ego run far beyond those of a girlfriend. Constantly and paradoxically counteracting loneliness without waking the listener from his dream-world so that he doesn’t notice others like him are being cured in the same way in other rooms by exactly the same mass-produced record.

“We’re basically all the same, and we need the same things, but on the other hand we’re on our own when we die. Although we all have to die, but that will only be a small consolation at the time of your death.”

Paddy McAloon has spoken.

There’s no question that the man knows what he’s talking about. Having around him the feet – or should I say toes – of bandmate and girlfriend Wendy Smith all day, and sometimes thinking that these delicate toes – the big toe obliviously rubbing the second biggest – will one day go the way of all flesh without him being able to ever fondle them again – well that is a sharp reminder of mortality.

“I write my songs more or less in isolation. When they appear on a record, I have no control over what they become sociologically. I mean we have to admit it, our music appeals to students.”

Prefab Sprout are so delicate and fragile that they can please only the finer spirits, and usually even then it’s those with the most petty-bourgeois concerns, confused by their experiences in University. This can be contrasted with the “Kids-R-United” movement we see today in pop, not propagated by young people but by adults, whose hero, Springsteen, explains his audience are all just like him. A proletariat united by the idea a man is simply a man, unwilling to submit to a boot in his face, with no masters above him nor slaves below.

Proletarian rock’n’roll has thus safely arrived at its most static, most tautological and compliant level, however the perpetuation of petty-bourgeois self-awareness via intelligent pop music has reached a peak with Prefab Sprout, to a point where you can hardly say any more about it. Are there any alternatives to excite?

No. The third way between Springsteen and Sprout, which the good, blunt and brilliant, chart music of the Human League/Haircut 1000 vintage was beginning to explore is blocked. The heroic campaign against the ghosts of the past as fought out in the US underground is impressive, but not far away from reverting to Pub Rock. Let’s be bourgeois again then! Whatever happened to the once so carefully tended ego, lost while pogo-ing as if it were a bunch of rusty keys?

“I like Van Dyke Parks. I like the songwriters of the 70s. Many people compare us with Steely Dan, even if Americans can’t relate to this. But there is a crucial difference. The 70s were a very placid decade, our music is anything but comfortable, it is much stranger than Ry Cooder or Joni Mitchell, although we welcome the fact that people who had been into that now listen to us and enter in contact with the present day. But our music is relevant today, in very different times. And I have nothing in common with the New York/LA cynicism of Donald Fagen. I don’t come from a very sophisticated part of our country.”

Could our generation possibly wish for anything nicer than for in the middle of the 1980s that Paddy, born in 1957, could step forward to redefine the sensitive petty-bourgeois bohemian, an intellectual and atmospheric combination as fresh today as the Talking Heads were in 1977? What did we do to deserve this?

“You surely are / A truly gifted kid / But you” re only as good as / The last good thing you did / Where have you been since then? / Did the schedule get you down? / Hear you got a new girlfriend / How’s the wife taking it?” Petty-bourgeois realism is always best when it attempts to go beyond the limits of its consciousness. Paddy McAloon, composer of delicate melodies, who admits he loves to wallow in incomprehensible literary references, is no fan of the surreal bubbles of rock poetry.

“I’m careful with the word poetry. There are some images in the language I use, but what I’m thinking most when I write songs is how a word sounds next to the music. That’s why there are no lyric sheets with Steve McQueen. Words set to music aren’t poems. Most of my lyrics are factual.”

This is Prefab Sprout: idiosyncratic and eccentric, like an unborn lovechild of Nick Drake and Joni Mitchell, or Laura Nyros and John Cale, but rooted in the here and now and the factual. And that’s exactly the point where the comparison with the early Talking Heads – which Paddy doesn’t like (“I know they wrote good songs, but know things doesn’t stop me putting on a Michael Jackson record when I have the choice between the two.”) – and which can’t be applied to him personally applies. His mind is very specifically lower middle class, and his sentiments accurately reflect that, but instead of trying to shake them off, anarchistically, with variations and variety taken from elsewhere in the Songwriter’s Guild, Paddy overcomes the limitations of his mind. Like Flaubert.

Why this secrecy? Where does this knowledge come from? Out of ten thousand creative middle-class children, only one will confront his personal contradictions via the real rather than the imaginary. Is this because Paddy’s reality has had a certain quality from the outset, bringing it closer to the worlds an ordinary songwriter would have to imagine? Like Wendy’s feet?

Petrarch would eagerly have written a sonnet on the subject; a lugubrious novelist, eyes half shut from an opium induced stupor would gladly rave about the dialectics of cuteness, and poison the example of Wendy’s feet and indeed her entire essence. How first she keeps silent for half an hour, whispering on the phone, and appearing generally unobtrusive, only then to chatter and gossip with the homespun British women from the band’s management, clapping and patting each others limbs like workers leaving the factory. Heartwarming and venomous, this postmodern girlfriend. Maupassant would have loved to have turned it into a short story. And so would I.

But it’s not just Wendy, the singer, the girlfriend, this ethereal creature, who might have been the archetype for Paddy’s line about desire, a supposedly sylph-figured creature who changes her mind. No, above all, it’s Martin, his brother. Who, along with Paddy had the idea to form a band in the early 1970s. Two very different characters – there lies the puzzle. Individual idiosyncrasies eventually become cherished eccentricities. But two! Two idiosyncratic brothers who could have spent ten or fifteen years growing more whimsical, but evolved in the opposite direction and took the rare opportunity to express themselves in front of an audience. Here it is, our completely parallel universe to which a few doors have kindly still been left open – hard to detect, it’s true, but even Theseus had to labour, and what is art without labour? A self contained representation of the world, one that is not simply pleasing, but which prompts you, invites you, to examine its inner laws and rules and to seek out its bizarre intricacies. But a world established alongside our own, thereby helping to explain it, and wrapped in its ambience. One brother and another: Grimm, Humboldt, Fogerty, Winter and Colour Box, the Kremer twins, the Rummenigges for example. There are no exceptions to this rule, and even in politics it is recently becoming favoured: Vogel v. Weizäcker – you name them.

“The foundation of our band is our shared childhood. Many of the songs are ancient. The name ‘Prefab Sprout’ comes from a time when enigmatic names like ‘Grateful Dead; were common and I thought they had to signify something. I also wanted our repertoire to include similar puzzles. ‘Faron Young’ dates from the mid-70s when we played in the Newcastle clubs and we were arrogant. If you’re a young record without a record deal you have the right to be arrogant, and I was extremely arrogant. I’ve refused to play in front of people who were drinking. Not that I’m against drinking, we just didn’t want our music to be a pretext for cheap enjoyment. People weren’t supposed to simply enjoy our songs.”

Nice to hear that somebody today is not out to be danceable and diverting. How wonderful the notion of feeding off each others’ arrogance is, this brazen conspiracy of a BIG friendship that is endowed by family bonds. It can produce an extremely unhealthy, venomous, feeling of supremacy that eventually reverts into the cultivatedly quirky sense of mission which Paddy’s songwriter ego has brought itself to. It makes all the distance that someone speaks, lost in oblivion and floating on surrealistic clouds, occasionally and banally crashing down to the material world to trouble his peers with the same insights that go along with such crashes; or when someone looks down from the Mt Sinai of a transcended infantile arrogance. However fragile and quiet he is – it could otherwise degenerate into perilously socialistic language – it doesn’t matter. The larynx still coos with the infant-arrogance, perhaps the key quality pop music is able to produce.

What I know about Paddy I’ve found out recently, when talking to him, complacently indulging him in his little, hardly effusive, rants. But what moved me – an unemotional person, supposedly held fast in the current of intellectual orthodoxies – was “Steve McQueen”, this second album, which in comparison to last year’s “Swoon” is more mature, rounded, conventionally beautiful but a less quirky record in the final analysis. Not that I trust my feelings more than my wits, but Steve McQueen is musically so unique – most appropriately described as slightly disillusioned, rarefied mid-70s song-writing – and can hardly be compared to any other kind of music, except in terms of how its effect matches the effect of others. I’d like to mention the Shangri-Las, John Lennon, “Hunky Dory”. The sort of effect where pretentiousness reverts to wisdom, without redeeming itself.

Which is always sad, isn’t it?

So what I’ve learned has given me additional criteria and explanations to judge Paddy’s talents, and Prefab Sprout as an interesting psycho-dynamic unit, but I was already prepared for that so there’s no reason to deliver any message other than to say that in the music of Prefab Sprout, and very much like in similar great artistic creations, there is a quality I admire greatly. It says “You don’t need to understand what you desire”. There is nothing new about that. What you desire you can’t justify, what you can justify you won’t covet, a stupid old cognitive dissonance, a dull humming when it’s hammering itself home, but sounding perfectly wonderful, bright and blue, if the object of your own desire – let’s call it Prefab Sprout – provides a route to exactly what it is you desire about it.

Here it gets difficult – on the one hand preaching down from the mountain of transcended arrogance, on the other leaving freedom to your listeners because of your own fragility. Certainties and withdrawal, but these are the dialectics of Wendy’s feet.

Paddy: “Something is wrong with us songwriters. I don’t usually feel a sense of belonging to the current crop of songwriters – the Post—Costello generation, Roddy Frame and all that. Like I said before we’re more weird, we are strange and awkward. But one thing units the new songwriters which is that we all write songs about songwriting. We’ve all become so self-conscious. From Green’s “Wood Beez” [Scritti Politti]. So why might that be the case?”

Because of Thomas Mann? James Joyce? Because of Wendy’s feet? Because it’s still the damned 20th Century which with every ebb and flow of its culture demands a new meta-language? What do I know?

In these times of the self-conscious songwriter, and a general rediscovery of the lost American continent, it’s time to make the truth, with all its attendant implications, clear: the only popular genre that doesn’t sell units because of the music but because of the lyrics has since time immemorial been Country and Western. Prefab Sprout named their last single, “Faron Young” after an old country singer. And in all its fakery it sounds like Beatnik Bluegrass with a Zen-consciousness

“But I love black music. How banal lines are enough to convey great sentiments. I love Prince and Michael Jackson, I still don’t understand how it works, simple sentences can say so much. And I have to admit, I rather cling to C&W music, because I’m a man who likes words. On the other hand, country music is always very straightforward and often sexist and reactionary. The crucial difference between old and new songwriters is the way they deal with women. Old songwriters are always looking to get a cheer from the crowd of beer drinkers. “

It’s very French and very stupid to enthuse about parts of women. Taking a part for the whole is just as stupid in the erotic as the rhetoric. See also Eric Rohmer’s “Claire’s Knee”, where the guy who covets only the knee of the crying girl gets punished during the course of the movie, or rather returned to a deserved state of mediocrity. It will mark another of Paddy McAloon’s qualities that he cherishes more about Wendy than her feet.