I was asked this week whether at some point I might consider writing a book about Prefab Sprout. I get asked this question quite a lot, and it’s always flattering. The answer is that I have considered it, but I won’t do it. Let me try to explain why that is, and why I don’t feel it’s a worthwhile exercise.

I was asked this week whether at some point I might consider writing a book about Prefab Sprout. I get asked this question quite a lot, and it’s always flattering. The answer is that I have considered it, but I won’t do it. Let me try to explain why that is, and why I don’t feel it’s a worthwhile exercise.

Elvis Costello’s famous one liner that forms half the title to this piece is, like most glib one liners, only partly true. It is perfectly possible to write great books about music, or about painting, or about any other form of art. Architecture even. But he hints at an inner truth, which is that what the artist wants is for the work to speak for itself. All else is window dressing.

As I’ve been working through the various Sprout interviews, I’ve been struck how stories are told and evolve over time. Let me take an example: Paddy creating imaginary records as pieces of paper. The most developed form of this story has him writing lyrics in spirals on round pieces of paper in the hope they will somehow magically become LPs, but the story seems to have started with him spreading words on paper in a circle around himself in his room and picking them out at random to make lyrics, Bowie style. Then it became making fake album covers with written lyric sheets. In other words, the story and the perception changed in the telling from one thing to another. For me the Bowie method is the most likely, but I don’t know that for sure. I’d like the story of spiralling lyrics to be true. While there’s uncertainty, it’s interesting.

All the way through the interviews you see this blurring process happening. Faced with the same questions endlessly, the answers evolve from what was true to what is easy to explain with minimal effort while remaining reasonably consistent with previous answers. There are some performers – Dolly Parton being a great example – who have a mental database of prepared answers for interviews they can reel off pretty much verbatim. You can track them through every interview. Dolly is a brilliant songwriter and an exceptional human being, but her interviews have all the spontaneity of an automated customer services phone menu. “Press 1 for the story of how much it costs to look this cheap; Press 2 for the story of the many coloured coat;… etc”.

But the point is this: none of it is real. It’s part of the PR. It’s a sort of wrapper created around the real payload, which is the music itself. The people involved are giving as little as possible of themselves, because it’s not part of the deal to offer more than their art reveals.

This leads us neatly back to Bowie, and his final album. He is – was, it’s still hard to accept Bowie is in the past – not exactly reticent, and he had a public profile, but he was able to keep his greatest secret to himself, and brilliantly wrap his own death into his art. If you really zero in on it, what was shocking about Bowie dying was that we had no inkling it was about to happen. We were coming to know “Black Star” a little, it was a normal release as far as the world was concerned and we were starting to form theories about it, but all of a sudden, BANG! he was dead and it meant something entirely different. The incandescent power of “Black Star” comes precisely from the fact we didn’t know everything.

Yet we still have everything we had before from Bowie. We will no doubt have more in coming months and years as the archives are mined. We’ve lost nothing except a creative force that was largely slowing anyway and realistically might have produced one or two more albums at most. In reality, for us, nothing substantive has changed. Whereas for his loved ones, who knew things we didn’t about him, there is a real loss. We can’t, and shouldn’t, be part of that, however much we want to be. Usually biographies – particularly unofficial ones – try to situate fans in the place of family or friends, to fill in the gaps.

Anyway to return to Prefab Sprout and Paddy and Co… There is a carefully constructed back story. The main actors are very private people, and Paddy is at pains to change his appearance regularly so as not to be easily recognizable. He’s on record as saying he admires Robert de Niro for revealing nothing in interviews, and his wonderful letter on T S Eliot is clear in stating he believes the art is everything, the detail surrounding the artist is irrelevant and unhelpful for him.

Of course for the fan, that’s easy to say and less easy to live with, and Paddy himself doesn’t necessarily practice what he preaches. He’s an avid reader of rock biography. Curiosity is always part of the game for fans. I always ask myself what I’d do if I found myself in front of Paddy’s rubbish bins with no-one looking: would I turn into an A. J. Weberman and have a rummage? I can’t say I wouldn’t. No, that’s not true: I would. I’m sure I would. But that doesn’t mean it’s right.

But let’s say this digging in the trash turned up some amazing revelation that added clarity to a previously delicious ambiguity from the work itself, and I revealed it. Fundamentally that diminishes the work, it doesn’t enhance it. It’s like scratching off the face of an elegant and magical automaton to reveal the cogs and levers of the workings. At worst it’s self aggrandisement too, that’s really where Weberman took it, dancing spitefully on the shoulders of giants.

There are really two main approaches to biography. The memoir or officially sanctioned book versus the unofficial account. Both have high points and low points: Tracey Thorn’s “Bedsit Disco Queen” and Graeme Thompson’s “Under the Ivy” are wonderful, where Morrissey’s “Autobiography ” is an exercise in poor writing and score settling, Goldman’s book on Presley reveals more about the author than the subject.

But neither approach adds much. Official works simply extend the sanctioned story. Unofficial works rely on what the author can turn up by fair means or foul: the juiciest revelations can only really be obtained by stealth and trickery or come from people with an agenda of their own. Or else they become a procession of rather dull facts: this or that recording was done in this or that studio with this equipment on this date, and so on.

There is a third way which personally I’m much more in favour of. This is typified by David Kinney’s “Dylanologists”, where the subject is made a peripheral figure and the work proceeds by looking at the impact Dylan made on other, non connected, people in various thematic categories. That’s wonderful, because the story emerges anyway, but it tells us something interesting about ourselves as fans.

My approach on this site tries to be like that. I try not to introduce too much if any privileged knowledge. It’s not that I don’t “know things”. People do tell you stories, send you stuff, or it turns up during web trawls in some way. I prefer to tell the story as far as possible by an aggregation of items from the public domain. I don’t go around hunting down friends and family, and if I do interact with anyone in the “inner circle” I try to keep my curiosity in check and remember that privacy is important for everyone involved. I’m not saying this from a holier than thou perspective – I have as much if not more of an inner Weberman as anyone – just that there is something of a responsibility not to forget our heroes are also people. If they haven’t told the world something, it’s probable they don’t want the world to know.

And anyway you can’t know everything. I remember discovering a lot of information during family history research about an odd family split in which one child of a deceased couple became rich and privileged, and the other two were poor and had a difficult life, one dying in a workhouse. It’s easy to make inferences and judgements, which I must admit I did for weeks, but eventually I met someone who knew the whole story and it was completely unexpected and different. So in proudly presenting a fact somehow discovered, you risk misrepresenting the truth.

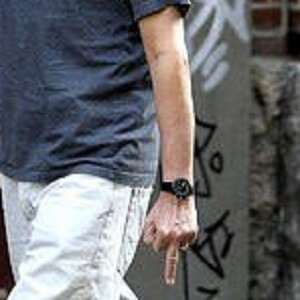

Bowie’s finger – for it’s Bowie reacting to a clandestine photographer in New York – in the illustration is a great shorthand for all of this: he may be a public figure, but there are lines you cross at your peril. I’m not writing the book.